|

| (American Veda by Philip Goldberg) |

R eading is a solitary thing. For the most part, nobody joins you in the process, save for the occasional elderly cat -i have one such- that takes delight in napping on top of the best paragraphs. But reading is also part of a breathtaking human process of experimentation; of taking things in and radiating back out; and not unlike inhaling and exhaling, there's a circulation of energy. So I'm grateful when readers step off the page to tell you about what books they've loved, letting ivory towers crumble...sharing ideas. So when a Shivers up the Spine reader suggested I get out and read American Veda by meditation teacher and ordained interfaith minister, Philip Goldberg, I was on it.

|

| (Bob Dylan) |

| ("Avatar", by James Cameron) |

|

| (Philip Goldberg) |

In our interview, Goldberg, a veteran interviewer himself (he completed several hundred interviews in the course of research for his book) offers his thoughts on why an interfaith perspective is crucial to understanding the variety of practices that have emerged out of the Vedanta and yoga contexts. Goldberg hones in on one of Vedanta's key messages "truth is one, its names are many", and explores how its message has reshaped not only American popular culture, but also the sheer range of religious expression and practices available to the average American. Seemingly immune to doctrinal differences, the collision of practices such as postural yoga, meditation, and self-help circles has resulted in one hell of a mash up; from Christian yogis to Kirtan chanting rabbis, Americans have inhaled a happy puff of yogic smoke and exhaled an electric cocktail of hybrid spirituality. Truth may be one, but its forms are many, many, many....

|

| (http://vagabondsister.blogspot.com/2010_09_01_archive.html) |

Priya Thomas Interview with Philip Goldberg, March 2011:

|

| (From Interfaith Ordination quilt. Artwork by Rev. Judith Coates) |

Priya: So can we just jump right into the book then? Is that cool?

Philip: Let's jump right in!

Priya: Ok awesome.

Philip: Are you recording this?

Priya: Yes. is that alright? Well you must be pretty used to this process since you did a lot of research for your book via interviews right?

Philip: Yeah, I did hundreds of interviews. So, you know I'm glad you're recording it. I'm putting myself in the other position!

Priya: Great! I'll start with the basics - why exactly did you write the book? What was the guiding idea behind taking up such a big project?

Philip: It's something that I've been part of, in observing and participating in since the 60's because my own life was transformed by Indian spiritual teachings; and as a writer, I've just been fascinated by its spread throughout the culture and in people's lives. And actually, the truth is if this doesn't take up too much time, I wanted to write this book in the 80's, and I wrote a proposal for it but was unable to get a publisher interested in it.

Priya: Oh that's right, you mention that in the book.

Philip: That's right, I do. Ah! see that was my way you see of testing you...(laughing)

Priya: (laughing) Ever the interviewer! You may have to get out of that old chair and switch positions here!

Philip: Alright! So anyway, in 2006, the religion editor at Doubleday Books had a similar idea and so by good karma, our paths crossed, through my agent and it was just the right time to do it. Then I set about doing the formal research because everything had been kind of informal prior to that.

Priya: Now the book has pretty much what I would see as an ecumenical mandate. And in fact, you make that clear at the end of the book where you talk about the teachings of Vedanta and Yoga having a specific gift to offer vis a vis the interfaith dialogue. Why do you think having an interfaith dialogue is so important right now?

Philip: Actually, I'd like to see it go beyond dialogue.

Priya: Ok.

Philip: But I think it's important to offer for the obvious reason that there's a lot of religious-based tension in the world. And we live in this world of instant communication and globalization where we're not just pluralistic societies in North America, but rather, we are pluralistic societies of the planet. And right now, increasingly so.... And people from different religious traditions and no religious traditions have a tremendous amount of misunderstanding and mistrust that arises and erupts in violence in some places or foolish tensions and hatreds. There's always been a need for people from different pathways to communicate with each other and understand one another better, and not just for the reasons of tolerance. I hate the word tolerance. I don't want to just tolerate other people; and I don't want to be just tolerated. I want to be respected. And I don't just want to understand others, but I want to learn from them. I want to have my own spiritual life enriched by by what they know and what they've experienced. And that's why I think it's terribly important to bring people together in intimate kinds of settings and not just lecture halls.

And the reason I think Vedanta and Yoga have much to contribute to this is two things: One, the sort of core Vedantic principle that truth is one, the wise call it by many names. It doesn't mean all religions are the same; which is the way the approach is often criticized. But it means that at the deepest part of spiritual experience, the inner life of religion when people go very deep into their connection to the sacred, that's where similarities occur. Beyond the level of dogma and doctrine and belief system, there's that inner connection to the divine or to spirit that - that's where everything converges. And people's reported experiences are very similar. And Vedanta points to that and highlights it; and the systems of yoga, the deep meditation practices and all the other components of yoga systems provide technologies for people to have those experiences and become aware of that inner oneness. That's probably too long an answer for you...

Priya: No no...you can answer however you like. I'm curious about the fact that the same "mystical" strands...if you want to call it that...exist within other traditions as well. So why would you focus on Vedanta or yogic philosophy? And would you accept that term mystical in terms of an experience of transcendent unity (just for the sake of agreeing on definitions?)

Philip: I'm happy to use it...

|

| (http://musingsofanightowl.blogspot.com/2008_10_26_archive.html) |

Priya: Ok but many of the other traditions, and I'm sure you're aware since you point them out in the book, have similar mystical strands running through them. For instance, when Christ says "the kingdom of god is within you" arguably, he's pointing to a similar interior connection to the sacred that you talk about in the book as Vedantic. So why were you specifically drawn to Vedanta?

Philip: With respect to an inter-faith dialogue, most of the other traditions have this approach as you mention, but they've kind of been obscured historically. They're now coming out with these more mystical teachings and and that's largely because of the presence, in the west, of prominent teachers from the east who stimulated the Christians and Jews, and probably now more and more Muslims, to look deeply into their own mystical traditions which have been obscured and unavailable for many, many centuries. But the other reason is that with Vedanta and with Hinduism in general, this notion that there are many, many legitimate pathways to the divine is right up front and centre. And it's not so evident in the other traditions. It's becoming that, but it's still only a few people on the fringes of Christianity or Judaism who are recognizing this. For the most part, they're still focused on theology, belief systems and doctrine which is where you find the differences among religions. And those need to be honored and respected, but Vedanta and yogic traditions point to an experience where western traditions are lagging behind. Am I making sense?

Priya: Yeah I understand. I think that makes sense. I just wonder would people who read St. John of the Cross have a different experience of that? But I see what you're saying in terms of the dominant conversation.

Philip: Yeah. The number of Christians who even know who St. John of the Cross is is very small.

Priya: So if I could ask you what your personal relationship to what you call "Vedanta Yoga" in the book is? Now, I know you talk about this in the book, but for those who maybe haven't read the book yet could you describe your personal process of coming to Vedanta and your own relationship to it as an interfaith minister? How do the ideas of yoga and Vedanta impact your work as a minister?

Philip: Well, I was raised by atheists who were Jewish by ethnicity in New York and I had no religious training. Actually, I was raised with disrespect for religion in general. And I was a young kid in the 60's trying to make sense of the world, and I was active in the anti-war movement and the civil rights movement, and I was just trying to get a handle on the big questions. And I found wherever I turned was unsatisfying until I found the teachings of the east. Not just the Vedantic strain of Hinduism but Buddhism and Taoism and all of what we think of as the mystical traditions from the east where the explanation of what human beings are, and what we might become, and how we might relate to the rest of the cosmos made a great deal of sense to me. And then the spiritual methodologies, principally meditation and also Hatha yoga were very attractive. I tried them on and they worked. They transformed my life and so I got more and more deeply into it.

My initial foray - well, there were many initial forays - but my initial spiritual home starting back in the 60's and running through most of the 70's was the Transcendental Meditation Organization.

That became my core practice and my community and I worked as a meditation teacher for some years. And then as time went on I availed myself of the full scope of spiritual teachings from the Vedantic and yogic tradition. And then I also started to realize that there was also much to learn from the western traditions as well. Especially, as you've suggested, you delve into the more esoteric branches of them. And, at a certain point I wanted to start doing spiritual counselling, and I thought of where I might get some additional training and I thought becoming an interfaith minister would make sense since I wanted to learn from all the different traditions and be able to work with people who come from different traditions. So the Vedantic perspective of there being many, many pathways to the truth and spiritual development guided that orientation and still does...

Priya: You interviewed Huston Smith...

Philip: I did.

Priya: That's a landmark interview...

Philip: Well it was and to my great pleasure and honor, he wrote the forward to the book.

Priya: I know I read it.

Philip: Yeah, and that was wonderful because you know he's probably what 92 or three now...and that he took the time to do it was just a great honour. Yes, but I interviewed him prior to that for the book. It was one of the highlights. Actually, I did about 300 hundred interviews over the course of the book; but there were certain ones that stood out more than others because of who the people were. And the one with Huston was especially sweet because it was done in person.

Priya: Now Huston Smith, you note, is one of the first scholars to really consider Hindu thought from the perspective of the practitioner's experience of their faith. Do you personally think it's important to consider the practitioner's experience of faith when writing about that faith and why?

Philip: Well, I can't think of anything more important.

Priya: Ok...

Philip: I mean most of the people who study comparative religion or scholars (well the approach in the west generally) is to focus all the time on beliefs and scriptural sources. So people analyze texts and then they make generalizations. So you hear people talking about Muslims all the time based on what they read in the Qur'an. But that does not take into account the actual living experience of the people who are actual practitioners of those faiths. And that's where you find a tremendous variety. The problem with looking at scriptures and just statements of doctrine is that you assume that all the people in them adhere to those things. Whereas I think that there's probably more variation within any particular religious group than there is across the different religions. Do you know what I mean?

Priya: Of course. Catholics around the world didn't and still don't conform to the pronouncements of Vatican 2 uniformly...It was the sixties after all...

Philip: (laughing) Yes, so you know what I'm saying. So that perspective of "what is it like to live these traditions"? and "what are the great variations within them"? I think that's a terribly important way to look at religion in general and one that hasn't been done enough.

Priya: So in terms of interfaith dialogue, do you think it might be important to really examine the experience of faith from a fundamentalist tradition as well...to see what its experience is offering?

Philip: That's a very good question. And I agree with you, if you're going to do it, you have to do it for the fanatics and extremists as well as the others. Otherwise, you don't fully understand it. In fact, there's much more variation within what we think of as fundamentalism than people realize and if we don't understand what it is that drives them, how can we counteract the more dangerous trends? And many fundamentalists are not dangerous at all. They just want to live their lives in their own way and we just need to understand that and the differences between them and the people who might be dangerous.

Priya: I noticed in the introduction you talk about the diversity of Hinduism as a practice and you talk about the term "Hinduism" as a regional construct that's the "equivalent of combining Christianity, Judaism and Islam and calling it Jordanism". I thought that was quite an interesting way of understanding its diversity. But when you look at the strains of Hindu thought that have taken root in America, would you say there were portions that were selectively chosen to suit America's own predisposition?

Philip: Absolutely right. That's what I use the term Vedanta Yoga in the book instead of Hinduism because of all of the huge variations within what we think of as Hinduism and all you need to do is go spend a little time in India and you see the mind-boggling varieties of Hinduism. But what caught on here, -and this was quite deliberate, smart and insightful on the part of the teachers who came here- were the core principles and precepts of Vedanta (and even Vedanta was quite simplified because there is much variety within Vedanta as well) and the methodologies of yoga. That's what was appealing to Americans. And the early teachers who came here all understood that. They were, for the most part, educated in schools influenced by British educational systems, they spoke English, they had equal grounding in Western education as they did in their own religious tradition, and they understood the modern, western mind. So they emphasized those scientific, pragmatic elements of the vast Hindu tradition. And that's what caught on here.

Priya: Do you think that the more highly adaptable a faith is, the more predisposed it might be to dilutions or misunderstanding? For instance, you note in the book that many Americans tend to call their religious experiences "spiritual" rather than "religious". Is that something that strikes you as evasive? Does the verbiage matter?

Philip: Well it's interesting. I think it matters, but how it will all play out will depend only in part on the language we use and the rest will be the effectiveness of the communication between representatives of yoga and Vedanta in the west and how people respond. Now your initial remark is very well taken. There is the possibility of dilution and we can see that. There's sixteen or more million Americans who go to yoga classes. I would think that the majority of them are just there for reasons of health or physical fitness; not appreciating the full value of what the yoga tradition represents and the full range of teachings and practices that are available. And that's a potential for dilution. Even going back to the 70's, when meditation first became mainstream, you know, meditation is an enlightenment practice or a practice to develop consciousness. And it's now become a way to reduce stress and anxiety. Now, you could say that was another dilution. Or you could say these kinds of things are trivializations. On the other hand, they are legitimate applications of these methodologies, and many, many people who get into them for those reasons, end up discovering that there's a whole lot more to be had. And so it's a delicate situation of making teachings available on the level that they'll be appreciated; and also not losing the full spiritual and developmental potential of these practices. And I'm optimistic because I think the people I'm in touch with in the yoga world are very aware of this.

Priya: Right.

Philip: In fact, I was just invited to speak at the annual festival of Yoga Alliance which is a professional association of yoga teachers precisely because the people running it want the historical perspective I give in the book to be communicated. So there are efforts to make sure that in this adaptation, that the full picture is retained. Now the language is a different issue. That may change. There are people teaching - and this is a big part of the book as you know - yogic practices and Vedantic principles and not using a word of Sanskrit or anything that seems Indian at all. Language can change. You get the point.

|

| (Siva, god of destruction) |

I'm wondering why Vedanta Yoga's influence results in a preference for easy imagery? Is the result of the influence of yogic ideas in America a happy-go-lucky vision of things that has little ability to confront violence or the more disturbing elements of any tradition? Hindu thought has its fair share of destruction and sacrificial imagery - I'm thinking of the Hymn to Prajapati, the primordial sacrifice in the Rg Veda, for instance, where creation itself is the result of self-immolation. So some might say that the idea of violent sacrifice exists in the Vedas just the same as it does the sacrificial lamb literature of the Bible.

Philip: You're good Priya. I have to just say I'm not normally interviewed by such well-informed people.

Priya: Oh. thank you. That's kind. But you might just be trying to distract me (laughing!)

|

| (Shri Mahabodhi Vihara, Bodh Gaya, Gautama Buddha) |

Priya: Right...

Philip: But I think the guy whom I quoted, was thinking of it as "Christ died for our sins" kind of ordinary Christianity. In the Hindu tradition all that destruction imagery is usually presented in the context of the destruction of ego and harmful tendencies in service of higher growth and spiritual development. And that's similar to the way Christian mystics would describe the crucifixion symbolism. It's just that in the Hindu world, that's understood by ordinary people. Siva is not just this ferocious God...Kali is not just bloodthirsty...it's in the service of spiritual development. And it's understood to be a process that we mirror in our own growth.

Priya: Its funny I think, that the strands of Hindu thought that have been absorbed in North America have been interpreted with a kind of unmitigated optimism. And you talk about how books like Think and Grow Rich or The Secret owe their persuasive power to Vedanta Yoga. What's your take on the flagrant optimism of those writings?

Philip: Well, you know I had big issues personally when "The Secret" came out and certain people who were presented as spokespersons for it had been people I know. And I thought it was trivializing what could be important principles. I mean, suddenly people could wish for gigantic houses? What is that about...in the service of materialism? And many of those people regretted that they participated in something that ended up the way it did. And others just said, "Well that gets people in the door". "You tell people you can have what you want and then you tell them there's more to life". And the whole purpose of these deeper teachings is to be happy and fulfilled whether you get what you want in the material world or not. So that was their take on it. But I know where you're going with this question. These are sort of the materialist equivalents of using yoga to look better. To me, all these yogic teachings, buddhist teachings, all the mystical teachings, are there to tell you that happiness is within you, and fulfillment is within you, and not in all the other stuff. All the rest is transient.

|

| (The Beatles, India 1967 photo: Paul Saltzman) |

Philip: A big part of what happened in the 60's especially when The Beatles went to India and meditation became "hot", - and it's fascinating when you go back and look at the newspaper coverage of all of that - is that it was was being widely reported that young people were getting off of drugs and meditating and doing yoga instead. And this was a very big deal that helped the legitimization of these things. But of course, drugs continued to be used in large numbers. And in fact, drugs began to be a bigger problem because they began to get adulterated, contaminated and there were a lot of casualties. The other side of it was that some people began to understand what was going on when people took entheogens like LSD and had these breakthroughs and powerful mystical experiences. And some people, because of the influence of teachings from the east, started to understand those experiences in a larger context of spiritual development. And now there's a vast body of literature about the spiritual uses of those drugs. So you know it had a mixed blessing effect. You think about Huston Smith who only ten or twelve years ago published a major scholarly book about entheogens and their role in spirituality.

Priya: You mention "Star Wars" in the book and talk about know George Lucas had read Joseph Campbell's Hero with a Thousand Faces. I'd always wondered when I watched that movie why the characters were so familiar! So I guess Americans were being exposed to these archetypes unaware...Do you think Americans are now ready to recognize these archetypes or do you think there's a good reason that popular culture in general tends to cloak or repackage the universality of certain ideas?

Philip: Well I think that's what artists do...The whole point of Campbell's Hero With a Thousand Faces is that these show up in every culture throughout time. So why wouldn't it be in a science fiction fantasy? To some people it's just good storytelling and nothing more. And Campbell would have said it's an unconscious thing. He was discovering that a structure emerges from the collective consciousness, or the deep inner, intuitive thought processes of storytellers. So it's not always a conscious process, but sometimes it is. Like you get JD Salinger putting Vedantic principles into the mouths of characters and you know that he studied at the Vedanta Centre and it was a deliberate kind of thing. Another example is George Harrison's lyrics where you could tell he was studying with Hindu teachers. But you know that's what artists do, they adapt things...

So your question about the source...well that's an interesting thing. One of the big points of my book is that people in the west have been powerfully affected by these teachings without even knowing there's anything Indian about them. People have been going to self-help seminars since the 1970's not knowing that some of the people who are teaching these forms of self-improvement of one kind or another were deeply immersed in Buddhist or Hindu teachings, and then consciously adapted some of those principles and removed all the eastern-sounding or foreign sounding language.

Priya: I thought the section in the book that dealt with Judaism and Vedanta Yoga was quite interesting. And I didn't know until you mentioned it earlier in this interview that your background is Jewish.

Philip: I'm from Whoopi's side of the Goldberg family!

Priya: (laughing) Right! You cite a few reasons in the book as to why Vedanta Yoga might have taken root in Jewish America. Among them were a severed connection with Judaic mysticism, and the impact of the Holocaust on familial ties to religious practice. What's your own personal sense of the reasons for the gravitation within the Jewish community to these ideas? We seem to be living in an interesting time where, as you mention, there are cross-pollinations happening and a dialogue between Judaism and Vedanta is playing out. Case in point, you mention people like Rabbi Rami Shapiro, who has been bringing Vedanta and yoga back into his synagogue.

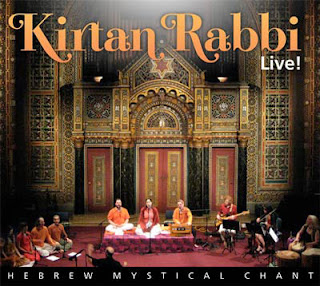

Philip: Again, a very good question. It actually just came up last night. I gave a talk at a university. The professor who hosted it, well that's actually one of her specialties. It's fascinating...just yesterday I got an email about an event taking place here in LA tomorrow night at a synagogue in Beverley Hills featuring the Kirtan Rabbi. And it's a rabbi who is on the circuit doing Kirtan at places like synagogues and elsewhere using traditional Indian musical motifs of call and response and traditional instrumentation and rhythms, but using Hebrew instead of Sanskrit.

Priya: That's quite something...

Philip: It's fascinating. He's not the only one, but he's now out there...and they're calling him the Kirtan Rabbi. And it's all very explicit; you can google him and see him on YouTube and that sort of stuff. And then there's also people like Rami and other Kabbalah teachers who were powerfully influenced by Buddhist and Hindu teachings and then went back and looked at the mystical foundations of their own tradition that had gotten lost in time, and are conscientiously reviving them.

Priya: So you think in the same way that say Christian teachings have lost their connection to their esoteric or mystical traditions, that possibly the Judaic tradition has suffered from that same process?

Philip: Yes. Same thing. In the Christian tradition those losses had to do with their own particular histories and the history of the Catholic Church and the Protestant Reformation, and corruption in the papacy and all kinds of other things. Because even hundreds of years ago Christian mystics were not exactly treated in a friendly manner by the establishment. And so these things got suppressed. I mean these teachings that are deeply esoteric and require a dedication to practice are not going to be picked up by everybody whose need for and interest in religion might be more prosaic or mundane. But now these teachings are being democratized so in Judaism, Kabbalah, which used to be this very esoteric thing, that was only for men of a certain age and certain educational qualification, now anybody can practice some of these Kabbalic teachings. So they are being democratized partly because the meditative practices from the east were catalysts for them to find the same things in their own traditions. Originally, mystical practices were not only not taught, but they were discouraged.

Priya: In terms of Hinduism as well, as I understand, it took took quite a while to re-absorb certain mystics back into the canon. They were, as most, considered heretics at the beginning.

Philip: Yes, that's right. And, many of the teachers who came to the west and became very famous for teaching meditative practices they were actually iconoclasts and there were traditionalists in India who were saying that they shouldn't be doing this. That this is not for the westerners, it's only for born Hindus, and not even all of them...just Brahmins and just men and all that kind of exclusivism. And these iconoclasts democratized the teachings which is, as we've spoken about, kind of a modern trend.

Priya: And I guess one could similarly argue that the same happened with Hatha Yoga as well. Now anybody can practice yoga; at intervals of your own choosing, with the studio or teacher of your choice...Coming and going as you please... that's a very different model than would originally have existed.

Philip: Well that's what makes sense though. That's what happens when you import something into a culture. They will adapt it in their own way. In the modern, western world of Americans and Canadians and Western Europeans, it's kind of a pragmatic attitude. If something works, we'll adopt it and we will adapt it to our own needs and thank you very much!

Priya: I don't know if you were following the surge of heated debates that arose over the last year as to whether Christians can, or should do yoga...the arguments were coming primarily out of the evangelical communities in the US...

Philip: I blogged about it. (read it here)

Priya: Ok well then based on the fact that Americans are adopters and adapters, does the fact that such arguments are arising strike you as ridiculous?

Philip: (laughing) Yes it does! Though I didn't use that word in my blog.

Priya: What do you think about that discussion? I did notice that as the discussion circulated through the blog world, the perception that Christianity and yoga were somehow at odds seemed to gain momentum. Most of those responding cited doctrinal differences between the traditions.

Philip: First of all, if Christians want to practice yoga and get something out of it, and it just makes them feel better or is good for their health, why shouldn't they? And if some of them want to practice yoga and find that it deepens their relationship to Christ, isn't that a good thing? And those two reasons for practicing are very common.

Priya: Right.

Philip: So what's the big deal? To me that's the foolish thing about it. These teachings could be understood in a religious context, they could be understood in a context of philosophical speculation, they could be understood as psychology, used as mind-body practices. You know, you can adapt them in any way that makes sense. And there's sixteen million people practicing yoga; I think it's a good bet that most of them are of Christian background given the population demographics. So to me it's all just a lot of noise.

|

| (weheartit.com) |

Priya: There's a stat in the book, and I think I've come across it before as well, that 40% of Americans report having had transcendent experiences. That's a pretty big number.

Philip: It is. And you wonder what it means. You know I'd love to see if one day there's follow up studies to see exactly what they mean by that...

Priya: Right. (laughing) Well I was going to ask you what you thought!

Philip: Well it's hard to know but it could mean that they just had a feeling of oneness while walking in nature, or having sex or something, or some intimation of something larger and a connection to something beyond their bodies, or a vision...It could be any of a number of things. It's hard to know how these things are defined in their surveys. But it doesn't surprise me.

Priya: As a minister, would you say that that experience of the transcendent or that experience as you said of "oneness" with something larger is something that is important to you personally?

Philip: Oh my god! it's what I feel my life is built around. To me that's the foundational component of life; that connection to the bigger cosmos or God or whatever you want to call it. That's one of the reasons we are here...to enlarge our identities beyond this limited ego. The more grounded I am in that, the more that experience becomes not just an experience, but a lived part of life, and the more fulfilled I am, the happier I am, and the more I feel like I'm growing. So to me that's fundamental it's not just something that you just hope happens, it's something to cultivate. It's just like you cultivate good health. To me, that's just spiritual wellness. The connection to the transcendent is just part of healthy life.

~

A merican Veda is a remarkable book precisely because its author has a stake in the American conversation. In acknowledging Vedanta and yoga as the source of countless faith movements, works of art, and mind-body practices, Philip Goldberg's approach provokes a dialogue that crosses America's faith boundaries. And as he points out, it's a conversation that will hopefully go further, to encourage interaction, understanding and respect across the varied traditions of its inhabitants.

Sure, it is arguable that the nature of the cross-pollinated "spiritual" conversation in America is so varied and adaptable that its concoctions often veer towards unidentifiable composites and naive miscellany. And as avid adopters and adapters of older traditions, North Americans could be criticized for occasionally reducing yogic philosophy for quick-fix, power-shake consumption. But the curious fact that a large percentage of Americans report having had transcendent experiences remains. And it is an indication that while traditional religious affiliation may be in decline, the quest for "one-ness" or the transcendent experience is still alive and kicking. And so Goldberg would argue that for those who seek, a very American translation of Vedanta is embedded in popular culture. And its practice methodologies - most commonly yoga and meditation - are proliferating, its infinite refractions ever alluding to a formless, single source.

|

| (weheartit.com) |

~

• Buy American Veda at Amazon.com

• Visit Philip Goldberg's site for upcoming lectures, events and to read his blog posts

• The American Veda Website

• Join the American Veda Facebook Page

Thank you for sharing this lovely and inspirational interview. I am an Australian and a traditional yoga teacher of 20 years or so.

ReplyDeleteI've just run foul of a Christian fundamentalist and thought I would see how other practitioners deal with this; that is how I came across your excellent site. This problem isn't uncommon, of course - Most yoga teachers have been persecuted for my perceived beliefs. And I constantly try to find ways to uphold an ancient tradition while living in a Western culture.

A couple of years ago some parents asked me to run a class for their children who attend a strongly Christian school - it was quite an interesting exercise. I truly believe that there are ways of teaching yoga for Christians without compromising the essence of our tradition.

The issues surrounding the transplantation of yoga are really complex. I look forward to reading Philip Goldberg's book and thank you for bringing it to our attention.

Oh, and I have a cat who quite deliberately sits on my current book.. it's a feline thing.

Hi anonymous, thanks for writing in. Sharing beliefs is tricky- let alone as a yoga teacher. All the best to you and that trickster cat. Pt

ReplyDeleteIt sure is.. You know, I believe so powerfully in what I do, but I defend the right of others to do the same. Why are we so threatened by difference?

ReplyDelete